Cinema arrived in Argentina soon after being launched in Paris and, in a short time, the first national productions started to be shot. Among other attractions, there were world-class pioneers in scientific and animation movies. But the true industry of argentine cinema started only in 1933, with the establishment of sound film. The good times, when the Argentine movies were watched all over Hispanic-America, lasted until the early 1950s.

Article of the guest columnist for surdelsur.com

Argentine cinema of ’50

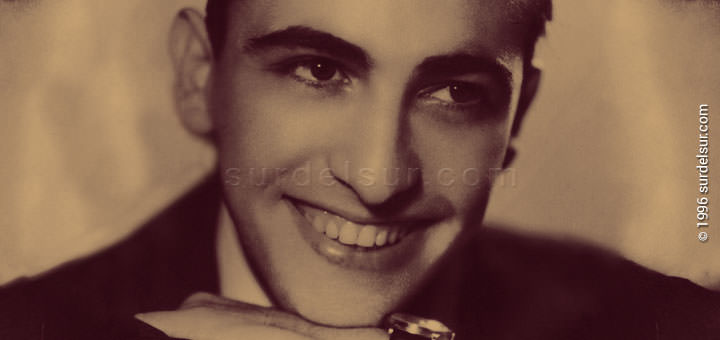

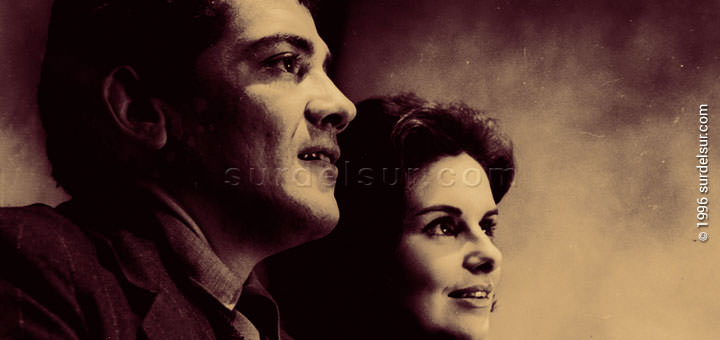

Afterwards, the gradual closure of the big studios, the growth of television, the stagnation of popular cinema and the isolation of auteur cinema imposed other rules. Los Isleros (Islanders, 1951) de Lucas Demare, protagonizado por Tita Merello y Arturo García Buhr, es un testimonio de comienzos de la decada del ’50. However, the quality of the singer, actor and filmmaker Hugo del Carril Hugo del Carril in Las aguas bajan turbias (Turbid Waters coming down, 1952), La Quintrala (1955) y Más allá del olvido (Beyond Oblivion, 1956).

In 1957 the Cinema Act and the Instituto Nacional de Cinematografía (INCA, National Cinema Institute), was created. Since then, this organization decides on credits, diffusion… or bureaucratic hindrances, according to the time involved. With its initial support Argentine cinema increases its production.

Its early support affirmed the controversial Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, who soon reached international fame with La casa del ángel (The House of the Angel, 1957) and La mano en la trampa (The Hand in the Trap, 1961); the couple made up by Fernando Ayala and Héctor Olivera, con El jefe (The Boss, 1958) and El candidato (The Candidate, 1959), creators of the Aries company.

The film of the Generation of ’60

After them, the members of the so called sixties generation, alien to the studio system, which was already too expensive and sluggish.

By that time, the most outstanding filmmakers were, Simon Feldman with El negoción (The Big Deal, 1959), David J. Kohon with Tres veces Ana (Three times Ana, 1961), Martínez Suárez with Dar la cara (To Face the Music, 1962), Lautaro Murúa with Shunco (1960) y Alias Gardelito (1961), René Mugica with Hombre de la esquina rosada (Man at the Pink Corner, 1962) on a story by Borges, and Manuel Antin with La cifra impar (The Odd Figure, 1962), about a story of Cortázar.

At the same time, Fernando Birri ran his school of documentary cinema, with two memorable works: Tiré dié (1960) y Los inundados (People in a Flood, 1962), where the realistic social charges and provincial humor made a good combination.

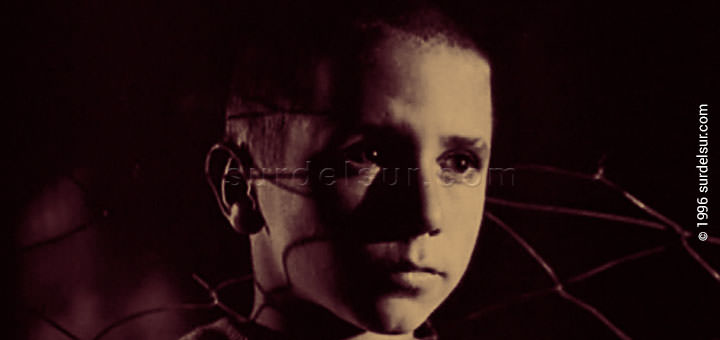

In these days there appeared another actor, singer and director: Leonardo Favio, who made his debut with an excellent drama, almost autobiographical, Crónica de un niño solo (Chronicle of a Lonely Boy, 1965). By the same time Rodolfo Kuhn performs the argentine movie Pajarito Gómez (1965), nominated for the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival.

Leonardo Fabio adds to his filmography, El Romance del Aniceto y La Francisca (The Romance of Aniceto and Francisca, 1967) and El Dependiente (Dependent, 1969).

By the same time Manuel Antín performs Don Segundo Sombra (1969). By late 1960s, some interest began to be aroused by the underground cinema of some advertising directors who experimented with cinema language.

Mainly the political essay by Fernando “Pino” Solanas y Octavio Getino en La hora de los hornos (The Time of Furnaces, 1968). Both filmakers belonged to Grupo de Cine Liberación and developed a provocative and innovative work which was forced to be exhibited in clandestine performances as a challenge to the military government. Much militant cinema was developed by those years.

Spring Argentine Cinema 1973-1975

Between 1973 and 1975, with a democratic government and a considerably stable economy, Argentine cinema reached great reviews and box-office success, such as the countryside drama Juan Moreira by Leonardo Favio; La Patagonia rebelde (Rebellious Patagonia, 1974) by Héctor Olivera, a story of repression; La tregua (The Respite, 1974) by Sergio Renán, an office romance nominated for the Oscar; and La Raulito (1975) by Lautaro Murúa. But censorship and a new military government put an end to this flourishing period.

The Argentine Cinema and his Time for Revenge

Recovery would come later, with Tiempo de revancha (Time for Revenge, 1981) by Adolfo Aristarain, a satire, Plata dulce (Easy Money, 1982) by Ayala, and the documentary called La república perdida (The Lost Republic, 1986) by Miguel Pérez.

In 1984, the government of the Radical Party did away with censorship and a filmmaker from the sixties, Manuel Antin, in charge of the INCA. Antin, promoted the birth of a new generation, which came to be called Cine Argentino en Libertad y Democracia (Argentina Cinema in Freedom and Democracy)

Thus, there came Camila (1984) by María Luisa Bemberg, another Oscar candidate; La historia oficial (The Official Story, 1985) by Luis Puenzo, final winner of the Oscar; Hombre mirando al sudeste (Man looking south-east, 1986) by Eliseo Subiela, El Exilio de Gardel (Gardel’s Exile 1985) by Pino Solanas, La deuda interna (The Internal Debt, 1988) by Miguel Pereira and many others, most by young or previously neglected filmmakers who won a large amount of international awards and distributed his movies almost all around the world.

However, the 1989 Argentine economic crisis, with hyper-inflation, also ended the new dreams.

Definitely turned into producer-directors depending on state subsidies or foreign co-productions, Argentine filmmakers have placed their hopes on the new Act, passed in 1995, forcing video and television to make financial contributions to Argentine movies. In this way. In the meantime, there is continuous appearance of young filmmakers, with great creativity and low budgets.

References:

All graphic material in this report is edited digitally. The customized version by surdelsur.com shown on this page is performed based on the following documents:

- Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducros Hicken .[Photographs and ancient prints] kindly granted by Pablo C. Ducros Hicken Cinema Museum